The Crucible of Genius: Puccini Before the Opera House

Posted by Paul Wood on 17th Oct 2025

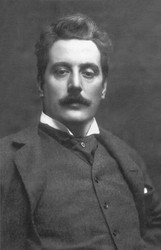

Before Giacomo Puccini conquered the stage with heartbreak and high notes, he was just another diligent student, albeit one whose homework occasionally sounded suspiciously like a future opera hit. Between 1874 and 1883, Puccini crafted a series of non-operatic works that, far from being mere academic assignments, served as the test kitchen for his later dramatic genius. From Lucca’s church lofts to Milan’s conservatory corridors, these youthful compositions trace the making of Italy’s next great maestro.

Between Lucca and Milan: From Hymnbooks to Harmony Classes

Puccini’s early years in Lucca were devoted to church music, where incense met counterpoint. But his move to the Milan Conservatory changed everything. There, under Antonio Bazzini and Amilcare Ponchielli, he swapped sacred routines for symphonic rigor. Milan demanded structure, discipline, and long nights perfecting fugues, hardly the stuff of passionate arias.

Yet, out of this tension grew a dual identity: the dramatist and the technician. Works like the String Quartet in D Major and the Preludio sinfonico polished his academic craft, while the smaller Liriche (art songs) revealed the lyrical soul that would soon reach the world’s grandest opera stages. In Milan, Puccini didn’t abandon Italian lyricism, he reverse-engineered it to stand alongside Wagner and the French symphonists.

Sacred Music with a Theatrical Edge

Even in his church music, Puccini couldn’t resist adding a bit of drama. Compare Vexilla regis (1878) with Salve del ciel regina (1880–82), and you can hear a young composer breaking free from his hymnal chains.

Vexilla regis is academic through and through—an A–B–A structure as rigid as a church pew. But just two years later, Salve del ciel regina moves with continuous flow. Puccini keeps the same key (F Major), blurs sectional boundaries, and gives sacred music a distinctly operatic shimmer. It’s as if Verdi had wandered into Sunday Mass.

The Lost Cantata That Found Its Voice

Long before La Bohème, Puccini tried his hand at patriotic grandeur with I Figli d’Italia bella (1877). Composed at nineteen for a competition in Lucca, this cantata gathers solo tenor, choir, and orchestra into a youthful anthem bursting with melody and enthusiasm, if not yet subtlety.

Once thought lost, the score resurfaced only recently, the missing solo line rediscovered and the piece republished in 2019. It reveals a composer who already understood that theatrical power lay not in spectacle but in the direct impact of melody. Even without the stage, Puccini was clearly thinking in spotlight-sized gestures.

The Workshop of Melos: Art Songs as Operatic Sketches

By the early 1880s, Puccini was writing liriche per canto e pianoforte—short songs like Melanconia, Storiella d’amore, and the now-famous Mentia l’avviso. These aren’t salon trifles; they’re blueprints for entire operas.

Mentia l’avviso is especially revealing. Structured like a recitative and aria, it experiments with chromatic harmonies and tonal fluctuation—musical devices that heighten emotional tension. The real punchline? Puccini later lifted its main melody wholesale to create Des Grieux’s aria “Donna non vidi mai” in Manon Lescaut (1893). Recycling, it seems, was Puccini’s secret superpower.

Lessons from the Quartet and the Symphony

Back at the Conservatory, Puccini’s teachers insisted he master chamber and orchestral forms—disciplines Italy had largely neglected in favor of opera. The String Quartet in D Major (1881–83) forced him to tame melody into counterpoint, learning how to make each line sing even without words.

Then came the Preludio sinfonico in A Major (1882), his final student examination. Scored with Wagnerian ambition—complete with English horn and tuba—it sounded more like an opera overture than a symphonic experiment. Critics at the time found it “restless” and “too long,” but even they had to admit its melodic strength. The formal design faltered; the Puccini touch did not.

Recycling Genius: The Economics of Emotion

Puccini’s habit of reusing his student material was not laziness. It was strategic resource management. When an idea worked, he simply waited to give it a better stage.

Melodies from the Preludio sinfonico later reappeared in his early operas Le Villi and Edgar, while themes from Mentia l’avviso became the beating heart of Manon Lescaut. What failed as structure triumphed as drama. It’s as if Puccini’s melodies knew their destiny all along—they just needed an opera house to breathe.

From Classroom to Curtain Call

Between 1874 and 1883, Puccini wasn’t merely learning the rules of composition; he was figuring out which ones he’d later break to make audiences weep. The String Quartet gave him the technical grounding, the Preludio sinfonico taught him orchestral color, and the Liriche honed his emotional intuition.

By the time he wrote his first opera, the ingredients of verismo—unbroken musical flow, emotional immediacy, and melodic intensity, were already simmering. Puccini’s genius was not sudden inspiration but patient distillation: a young composer turning conservatory exercises into the blueprints of operatic immortality.

And if his professors ever marked him down for excessive theatricality, history has since given him full marks for drama.

Recommended Listening

Get to know Puccini’s formative years with these essential tracks and scores

-

Vexilla regis

Sacred duet with organ—listen for the classic A–B–A shape and sturdy liturgical style.

-

Salve del ciel regina

A Marian anthem, already glowing with operatic lyricism. Spot the continuous melodic flow.

-

Mentia l’avviso (1883)

Art song meets opera aria. Direct ancestor of “Donna non vidi mai” from Manon Lescaut.

-

String Quartet in D Major

Puccini flexes his contrapuntal muscles. A rare journey into chamber music.

-

Preludio sinfonico in A Major

Academic symphonic fireworks—plus the seeds of future operatic themes.

All these works illustrate how the seeds of Puccini’s genius grew long before the curtain ever rose. Happy listening—and happy score hunting!